The factory pattern - Design patterns meet the frontend

Picture this. A car dealership is selling cars 🚗. Suddenly, they want to branch out and sell trucks 🚛. However, you had initially programmed the order and sale system to handle cars. What do you do now? Do you duplicate the majority of the business logic in the system to also handle trucks specifically?

Sure, it’s a somewhat quick win to do this. However, a short while later, the Dealership decides it’s going to start selling Motorbikes.

🤦 Oh no. More code duplication? What happens if the order system needs to change, do we need to update it now in three places!!?

We’ve all been there. It’s hard to predict when this situation might occur, but when it does, know that there is a solution that may initially require a bit of refactoring, but will surely mean a more maintainable solution, especially when the dealership says it’s going to start selling Boats! 🛥️

In this article, we will discuss:

- 💪 A solution - The factory pattern

- 🤔 When should I use it?

- 🤯 Some advantages and disadvantages

- ❓ Where is it being used in the frontend world?

- 🏭 Let’s see an example!

💪 A solution - The factory pattern

The factory pattern is a creational design pattern that adds an abstraction layer over common base behavior between multiple objects of a generic type.

The client code, the code that will use this layer, does not need to know the specifics of a behavior’s implementation, as long as it exists.

If we take our car dealership turned multi-vehicle dealership example above, we can see that the common ground between the cars, trucks, and boats is that they are all vehicles. The OrderSystem within the dealership only needs to work with a base Vehicle, it does not need to know the specifics about the Vehicle being processed.

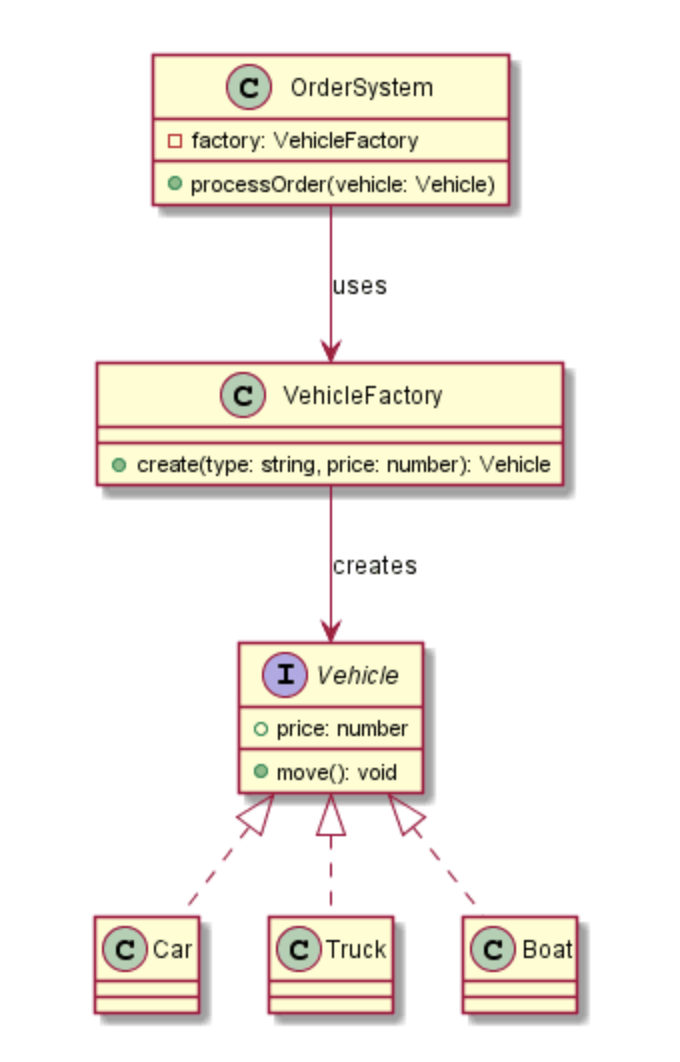

Let’s take a quick look at a UML diagram to illustrate this:

As we can see from the diagram, the system contains concrete implementations of the Vehicle interface. The OrderSystem doesn’t know or need to know what these concrete implementations are; it simply relies on the VehicleFactory to create and return them when required, therefore decoupling our OrderSystem from the Vehicles that the dealership wants to sell! 🚀🚀🚀

Now, they can branch out to as many vehicles as they like, and we only ever have to create a new implementation of the Vehicle interface and update our VehicleFactory to create it! 🔥🔥🔥

🤔 When should I use it?

There are a few situations, other than the one I described above, where this pattern fits perfectly:

- Any situation where you do not know the exact type or dependency that a specific portion of your code needs to work with.

- If you are developing a library, using the factory pattern allows you to provide a method for consuming developers to extend its internal components without requiring access to the source itself!

- If you need to save system resources, you can use this pattern to create an object pool where new objects are stored when they do not already exist. This way, when these new objects do exist, they will be retrieved instead of being created from scratch.

🤯 Some advantages and disadvantages

Advantages:

- It avoids tight coupling between the consumer of the factory and the concrete implementations.

- In a way, it meets the Single Responsibility Principle by allowing the creation code to be maintained in one area.

- It also meets the Open/Closed Principle by allowing new concrete implementations to be added without breaking the existing code.

Disadvantages:

- It can increase the complexity and maintainability of the codebase as it requires a lot of new subclasses for each factory and concrete Implementation.

❓ Where is it being used in the frontend world?

Surprisingly (well maybe not), Angular allows the usage of factories in their Module Providers. Developers can provide dependencies to modules using a factory, which is extremely useful when information required for the provider is not available until runtime.

You can read more about them in the Angular Docs for Factory Providers.

🏭 Let’s see an example!

A great example of this in the frontend is cross-platform UIs.

Imagine having a cross-platform app that shows a dialog box. The app itself should allow a Dialog to be rendered and hidden. The Dialog can render differently on a mobile app than it does on a desktop. The functionality, however, should be the same. The app can use a factory to create the correct Dialog at runtime.

For this example, we are going to use TypeScript to create two implementations of a Dialog, a MobileDialog, and a DesktopDialog. The app will use the User Agent String to determine if it is being viewed on a desktop or mobile device and if it will use the Factory to create the correct Dialog.

Note: Normally, it is more ideal to develop one responsive

Dialog; however, this is an example to illustrate the factory pattern.

Let’s start by creating a base Dialog interface:

interface Dialog {template: string;title: string;message: string;visible: boolean;hide(): void;render(title: string, message: string): string;}

This interface defines the common behaviour and state that any concrete implementation will adhere to.

Let’s create these concrete implementations:

class MobileDialog implements Dialog {title: string;message: string;visible = false;template = `<div class="mobile-dialog"><h2>${this.title};</h2><p class="dialog-content">${this.message}</p></div>`;hide() {this.visible = false;}render(title: string, message: string) {this.title = title;this.message = message;this.visible = true;return this.template;}}class DesktopDialog implements Dialog {title: string;message: string;visible = false;template = `<div class="desktop-dialog"><h1>${this.title};</h1><hr><p class="dialog-content">${this.message}</p></div>`;hide() {this.visible = false;}render(title: string, message: string) {this.title = title;this.message = message;this.visible = true;return this.template;}}

There are only slight variations in this functionality, and you may argue that an abstract class would be a better fit for this as the render and hide methods are the same. For the sake of this example, we will continue to use the interface.

Next, we want to create our DialogFactory:

class DialogFactory {createDialog(type: 'mobile' | 'desktop'): Dialog {if (type === 'mobile') {return new MobileDialog();} else {return new DesktopDialog();}}}

Our factory takes a type and will subsequently create the correct implementation of the Dialog.

Finally, our App needs to consume our factory:

class App {dialog: Dialog;factory = new DialogFactory();render() {this.dialog = this.factory.createDialog(isMobile() ? 'mobile' : 'desktop');if (this.dialog.visible) {this.dialog.render('Hello World', 'Message here');}}}

Looking at the code above, we can see that the app does not need to know about the concrete implementations, rather, that logic is the responsibility of the DialogFactory.

Hopefully, this code example has helped to clarify the factory pattern and its potential usage in the frontend world.

Personally, I understand the concept and the advantages of this pattern, but I do not like the focus and reliance on inheritance that is required for its implementation.

Feel free to discuss any other examples or your own opinions of this pattern as I’m still undecided on it. If you have any questions, feel free to reach out to me on Twitter: @FerryColum.

Free Resources

- undefined by undefined